Wouldn’t it be awesome if you could update your game’s assets while your app is running? It turns out you can, and it’s not even very complicated.

Whether you want to tweak a game setting or experiment with a variety of image styles on the fly, this will be one of the things you wish you had been using all along! Either for faster development or as a design feature for your game.

In this case, we’ll build a New York Traffic Webcam viewer with Cocos2D. You will learn how to download files to your app at runtime with the iOS SDK and cocos2d-iphone, and how to check if the file on the web server has actually been modified.

In this case, we’ll build a New York Traffic Webcam viewer with Cocos2D. You will learn how to download files to your app at runtime with the iOS SDK and cocos2d-iphone, and how to check if the file on the web server has actually been modified.

Along the way you’ll understand how to use the Mac OS X built-in web server to speed up your development by replacing game assets on the fly. By copying files to a specific directory on your Mac you can make immediate changes to your running app!

And you don’t need any experience with HTML, Apache, or any other web server or web services technology. In fact, I consider myself to be an web-illiterate because I’ve hardly done anything programming-related with web services and servers in the past.

As usual, the project is available from my LearnCocos2D github repository under the MIT License. The project’s name is Cocos2D-UpdateFilesFromWebServer. To improve readability of the article I removed error checking from the code in the article.

I took Mike Ash’s performance measuring code from 2008 with the improvements made by Stuart Carnie in early 2010 and turned that into a performance measuring project for 2012.

I know it’s still 2011, consider this a forward-looking statement. In any case, the test project is available for download, ready to run, includes Cocos2D v1.0.1 and is relatively easy to modify for your own needs. This project is also available on my github repository where I host all of the iDevBlogADay source code.

Since numbers are so dry and hard to assess, you’ll find the rest of this post garnered with charts and conclusions based on the results obtained from iPhone 3G, iPod 4 and iPad.

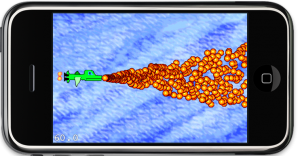

While writing the Learn Cocos2D book I was surprised to find that Cocos2D’s CCSpriteBatchNode was only able to increase the performance of several hundred bullet sprites on screen by about 10-15% (20 to 22.5 fps). I wanted to re-visit that scenario for a long time because as far as I understood, the more sprites I was drawing the greater the impact of CCSpriteBatchNode should be.

But even Cocos2D’s own sprite performance tests (compare columns 9 and 10) revealed a performance difference of under 20% (39 to 42 fps). It’s only when all sprites are scaled and rotated, or most of them are outside the screen area, that sprite batching seems to have a bigger impact (25 to 60 fps). Surely that scenario is not applicable to most games. So I started investigating.

I often start out with new code using dummy graphics. Until I figure out what exactly I need and what is going to work, I work with single image files added to the project’s resources. Creating a texture atlas is always the last step I do, once everything is settled. Creating and updating a Texture Atlas adds just a few extra steps but I always strive to avoid any unnecessary extra steps during a creative working period. Especially while experimenting. Any repetitive task hampers creativity.

But eventually, I will have to go in and change every CCSprite initialization code from spriteWithFile to spriteWithSpriteFrameName. Except, I don’t.

The following is a simple extension category for CCSprite that extends CCSprite with a spriteWithSpriteFrameNameOrFile initializer. It looks for the given file name in the CCSpriteFrameCache. If it exists as CCSpriteFrame, it uses that sprite frame and otherwise it reverts back to loading the sprite from file. Very easy, very helpful.

// CCSpriteExtensions.h

#import "cocos2d.h"

@interface CCSprite (Xtensions)

+(id) spriteWithSpriteFrameNameOrFile:(NSString*)nameOrFile;

@end

// CCSpriteExtensions.m

#import "CCSpriteExtensions.h"

@implementation CCSprite (Xtensions)

+(id) spriteWithSpriteFrameNameOrFile:(NSString*)nameOrFile

{

CCSpriteFrame* spriteFrame = [[CCSpriteFrameCache sharedSpriteFrameCache] spriteFrameByName:nameOrFile];

if (spriteFrame)

{

return [CCSprite spriteWithSpriteFrame:spriteFrame];

}

return [CCSprite spriteWithFile:nameOrFile];

}

@end

Chapter 6 - Spritesheets and Zwoptex

In this chapter the focus will be on Spritesheets (Texture Atlas), what they are and when, where and why to use them. Of course a chapter about Spritesheets wouldn’t be complete without introducing the Zwoptex tool. The graphics added in this chapter will then be used for the game created in the following chapter.

The chapter will be submitted on Friday, August 6th.

Anything about Spritesheets you always wanted to know?

Just let me know. I’ll be researching what kind of issues people were and are having regarding Spritesheets. I want to make sure that they are all covered in the book.

Please leave a comment or write me an email.

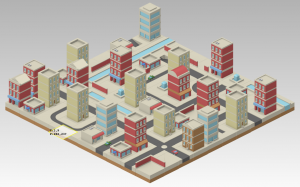

Summary of working on Chapter 5 - Game Building Blocks

I finally found a better title for the chapter. A big part is about working with Scenes and Layers. A LoadingScene class is implemented to avoid the memory overlap when transitioning between two scenes. Layers are used to modify the game objects seperately from the static UI. I explain how to use targeted touch handlers to handle touch input for each individual layer, either swallowing touches or not.

I finally found a better title for the chapter. A big part is about working with Scenes and Layers. A LoadingScene class is implemented to avoid the memory overlap when transitioning between two scenes. Layers are used to modify the game objects seperately from the static UI. I explain how to use targeted touch handlers to handle touch input for each individual layer, either swallowing touches or not.

The issue of whether to subclass CCSprite or not is discussed and an example is given how to create game objects using composition and without subclassing from CCNode and how that changes touch input and scheduling.

At the end the remaining specialized CCNode classes such as CCProgressTimer, CCParallaxNode and the CCRibbon class with the CCMotionStreak are given a treatment.

As you can see from the pictures, I’m also making good progress at becoming a great pixel artist. Only I have a looooooong way ahead of me still. But I admit, the little I know about art and how much less I’ve practiced it, I’m pretty happy about the results and having fun with it. The cool aspect of it is that this should be instructive art. It doesn’t have to be good. So I just go ahead and do it and tend to be positively surprised by the results. I’ll probably touch this subject in the next chapter about Spritesheets: doing your own art. It’s better than nothing, it’s still creative work even if it may be ugly to others, and it’s a lot more satisfying to do everything yourself, even if it takes a bit longer and doesn’t look as good. At least it’s all yours, you’re having fun, and learn something along the way. And you can always find an artist sometime later who will just draw over your existing images or who replaces your fart sound effects with something more appropriate.

Btw, if you’re looking for a decent and free image editing program for the Mac, I’ve been using Seashore for about a year now and I’m pretty happy with it.