Chapter 12 - Physics Engines: Box2d & Chipmunk

This chapter gives you an introduction to physics engines and what they can do. Since cocos2d supports two physics engines out of the box, Box2d and Chipmunk, I will explain how to do the same things in both physics engines and I aim to cover at the very least the basic elements like shapes, joints and collisions.

Because choosing either physics engine is often done on subjectively. Some developers may prefer the Object-Oriented C++ nature of Box2d while others may feel more comfortable with the C-based interface of Chipmunk (*). At the very least I want to present both and show their strength and weaknesses by example.

(*) Note: there is an Objective-C binding for Chipmunk made by Howling Moon Software. It’s free to use on Mac OS X and iPhone Simulator but costs $200 per title if you want to publish to the App Store. I believe that most cocos2d developers wouldn’t mind spending up to $30 on a tool or library that is essential, that is why I included Zwoptex and Particle Designer in the book. This product however is in a different ballpark price-wise.

On the other hand, the free Chipmunk SpaceManager also aims to offer better integration with cocos2d-iphone and promises a simplified Objective-C interface. I will have a look at the SpaceManager and then decide whether I’ll discuss it in the book, I say it’s likely. Another physics tool that has gotten some attention is the VertexHelper which I’ll at the very least will refer to.

Summary of working on Chapter 11 - Isometric Tilemaps

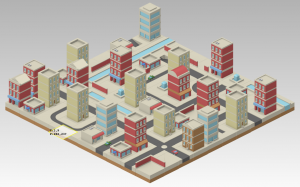

Isometric tilemaps rock! That is, if you can get all those nasty issues solved. Even though all the issues like graphics glitches at tile edges, correct z-ordering and the proper blend functions have all been discussed and solved by now, it’s still very challenging to get an isometric tilemap on the screen and a player walking over it, with no glitches at all. I believe this chapter will give a lot more developers the chance to delve into the exciting world of isometric tilemaps. I too learned a lot making this example game, and part of me now wants to write an old-school isometric RPG game. Again. For the n-thousand-th time. Sigh. Some day, some day …

Anyhow, the project I made over the course of this chapter features properly z-ordered tiles and a player sprite, which moves tile-by-tile over the isometric tilemap. You control the player by simply touching in the direction relative to the player that he should move to. One specialty of this project is that the player always remains centered on the screen, he doesn’t move at all! It’s simply the tilemap that is moved under him, which makes a couple things much easier.

Anyhow, the project I made over the course of this chapter features properly z-ordered tiles and a player sprite, which moves tile-by-tile over the isometric tilemap. You control the player by simply touching in the direction relative to the player that he should move to. One specialty of this project is that the player always remains centered on the screen, he doesn’t move at all! It’s simply the tilemap that is moved under him, which makes a couple things much easier.

Nevertheless you also learn how to find the tile coordinates for a tile that you touch on the screen. And how to avoid the isometric, diamond-shaped tilemap to show the “outside” of the world by adding a border around the tilemap and limiting movement to the playable area. Similarly, the blocking tiles like walls, mountains and houses all block the player’s movement by drawing over the map with a collision layer and a tile whose property is set to “block_movement”.

In the meantime, if you want to gain a better understanding of how isometric tilemaps work, I can recommend the Isometric Projection article by Herbert Glarner. And in case you’re wondering how I suddenly and dramatically increased my art skills, I’ll be honest: I didn’t. I used the terrific tilesets from David E. Gervais which are published under the Creative Commons License. It means you are free to to copy, distribute and transmit those tiles as long as you credit David Gervais as their creator. You can download these tiles from Pousse Rapiere’s website or you can directly download them all at once as 6.4 MB ZIP file here. If you like to hear it from the man, here’s a bit of insight and history from David explaining how these tiles were made.