A Sprite Sheet is of course a Texture Atlas (see Wikipedia). Simple, right?

Oh you wanted to know details? Like, why you should use sprite sheets? What the benefits are? How sprite sheets save memory?

Then watch the vividly animated “Sprite Sheets - The Movie, Part 1” (aka Essential Facts Every Game Developer Should Know) courtesy of Andreas Löw:

You can find the transcript of the video on this page and the tool that can do all that (and more) is TexturePacker.

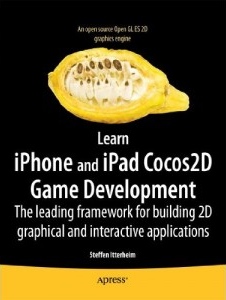

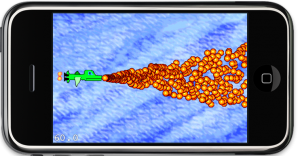

While writing the Learn Cocos2D book I was surprised to find that Cocos2D’s CCSpriteBatchNode was only able to increase the performance of several hundred bullet sprites on screen by about 10-15% (20 to 22.5 fps). I wanted to re-visit that scenario for a long time because as far as I understood, the more sprites I was drawing the greater the impact of CCSpriteBatchNode should be.

But even Cocos2D’s own sprite performance tests (compare columns 9 and 10) revealed a performance difference of under 20% (39 to 42 fps). It’s only when all sprites are scaled and rotated, or most of them are outside the screen area, that sprite batching seems to have a bigger impact (25 to 60 fps). Surely that scenario is not applicable to most games. So I started investigating.

Chapter 6 - Spritesheets and Zwoptex

In this chapter the focus will be on Spritesheets (Texture Atlas), what they are and when, where and why to use them. Of course a chapter about Spritesheets wouldn’t be complete without introducing the Zwoptex tool. The graphics added in this chapter will then be used for the game created in the following chapter.

The chapter will be submitted on Friday, August 6th.

Anything about Spritesheets you always wanted to know?

Just let me know. I’ll be researching what kind of issues people were and are having regarding Spritesheets. I want to make sure that they are all covered in the book.

Please leave a comment or write me an email.

Summary of working on Chapter 5 - Game Building Blocks

I finally found a better title for the chapter. A big part is about working with Scenes and Layers. A LoadingScene class is implemented to avoid the memory overlap when transitioning between two scenes. Layers are used to modify the game objects seperately from the static UI. I explain how to use targeted touch handlers to handle touch input for each individual layer, either swallowing touches or not.

I finally found a better title for the chapter. A big part is about working with Scenes and Layers. A LoadingScene class is implemented to avoid the memory overlap when transitioning between two scenes. Layers are used to modify the game objects seperately from the static UI. I explain how to use targeted touch handlers to handle touch input for each individual layer, either swallowing touches or not.

The issue of whether to subclass CCSprite or not is discussed and an example is given how to create game objects using composition and without subclassing from CCNode and how that changes touch input and scheduling.

At the end the remaining specialized CCNode classes such as CCProgressTimer, CCParallaxNode and the CCRibbon class with the CCMotionStreak are given a treatment.

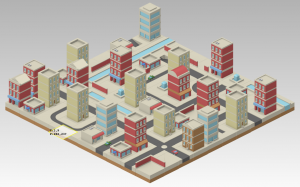

As you can see from the pictures, I’m also making good progress at becoming a great pixel artist. Only I have a looooooong way ahead of me still. But I admit, the little I know about art and how much less I’ve practiced it, I’m pretty happy about the results and having fun with it. The cool aspect of it is that this should be instructive art. It doesn’t have to be good. So I just go ahead and do it and tend to be positively surprised by the results. I’ll probably touch this subject in the next chapter about Spritesheets: doing your own art. It’s better than nothing, it’s still creative work even if it may be ugly to others, and it’s a lot more satisfying to do everything yourself, even if it takes a bit longer and doesn’t look as good. At least it’s all yours, you’re having fun, and learn something along the way. And you can always find an artist sometime later who will just draw over your existing images or who replaces your fart sound effects with something more appropriate.

Btw, if you’re looking for a decent and free image editing program for the Mac, I’ve been using Seashore for about a year now and I’m pretty happy with it.